Anyone who says nobody's perfect did not watch the 1972 Miami Dolphins. In figure-skating and other artsy competitions, scoring is largely an opinion – and often judging is questioned more than the identity of DB Cooper.

But in the smash-mouth world of football, perfection is not only attainable, it is indisputable. 17-0 is a record, not an opinion, and this incredible feat by the '72 Fins has not been duplicated for forty-five years...and counting. Abe Maslow called it Self-Actualizing; the top of your game, your spirit, your love of life.

For some reason I have been obsessed with excellence, and its all-elusive dance partner, perfection. In 1973, I wrote an essay featuring the Miami Dolphins, who had won the Super Bowl to cap the first perfect season in NFL history. It was Miss Green's English class in eighth grade, and reflecting on those ancient times, it was the first Greg Meakin Maslow Award I put on paper.

In that essay, Champions vs. Contenders, I pondered the differences between those that win, and those that come close but no cigar. In that Dorval High School essay, I threw in “perfection” comparisons to racehorse Secretariat, and my beloved Montreal Canadiens.

Football, like most sports, is driven by winning, but steered by statistics. With the evolution of technology, statistics in sports today are a micro-manager's dream – a sports wonk festival of analytical fun. There are statistics about statistics, and my question at the time, and remains today, is why certain teams and athletes seemed to win championships regardless of statistics, or other measurable formulas of analysis and prediction.

The very concept of the underdog winning despite the odds has created volumes of tales of victory and achievement over the years, and centuries. Indeed, the fabric and culture of our country is generously woven with an obsession for victory – especially victory that flies in the face of huge obstacles or “expert” prediction.

Goodness, the country's founding and survival itself fall into the category of unlikely long-shot. As a handicapper, I would have put the odds of the Americans defeating the British at 10-1. Surviving and thriving to this day as we have, as a feisty, independent nation – a million-to-one.

The 1972 Miami Dolphins are Maslow Award winners not by simply winning and attaining perfection, but by how they did it, and what they overcame. Statistically, they led the league in most categories, including points for and against. They had not one, but two 1,000-yard rushers in Larry Csonka and Mercury Morris. Paul Warfield, legendary wide receiver, averaged 20-yards per catch.

Big-time stats here, and the list could go on. But as I will share shortly, these stats were million-to-one odds by today's standards. They shouldn't have happened.

But boy, the stats were explosive with this team, on both sides of the ball. Csonka and Morris were polar opposite running backs. Csonka, straight up the middle for five yards every time. Five yards up the middle. Five yards up the middle. A forward-leaning cement truck plowing up the gut for his 1,000, at five yards a pop. Mercury Morris, a flashy, dynamic speedster, blazed to 1,000 yards and beyond with style and excitement. And Jim Kiick, reliable workhorse, pounding more carries than Zonk.

The Miami defense, nicknamed No Name due to its obscurity compared to the dazzling offense, was superb. Lowest points allowed at 171, for a ridiculous average of 12.2 points per game, they were a turnover machine with Jake Scott and Dick Anderson. Nick Buoniconti, Manny Fernandez, and the rest of the crew shut down offenses every Sunday.

But one catastrophe occurred during Miami's season that should have blown apart its statistics, and its chances of getting to the playoffs, never mind going undefeated and winning the Super Bowl. In my view, no team today could overcome the obstacle that faced the Dolphins in week five of 1972. The starting quarterback broke his ankle.

Star quarterback Bob Griese, who had cruised the team to a 4-0 start, and was coasting to an MVP trophy, broke his ankle and was out for the season. In our 2017 NFL, a Tom Brady, Aaron Rodgers, Russell Wilson, or the other elite QBs surely could not be lost to an injury and his team win a Super Bowl. No way. Not today.

Enter backup quarterback Earl Morrall, stage right. He strolled on the field and led his team to ten straight wins, as well as the playoff opener. Griese returned for one playoff game and the Super Bowl, topping off this magical sundae of a season.

Earl Morrall was the tipping point of the season. This thirty-eight year old signal caller, in my opinion, was the key to the 1972 Miami Dolphins becoming a first-round Maslow Award winner – as opposed to being a forgotten team, and maybe even banished to the golf course before the playoffs.

Unlike the vast majority of today's teams – the Dolphin's backup quarterback was a championship starter in disguise. Morrall was a wily veteran who had already won a Super Bowl for another team as a backup, the 1971 Colts, when he replaced Johnny Unitas.

Before the 1972 season, Miami coach Don Shula convinced ownership to acquire Morrall from the Colts as an “insurance policy” on Griese's health – despite the outrageous salary of $90,000 for a backup! Shula was indeed prophetic with this move, and of course has a huge hand in lifting this Maslow Award with his team.

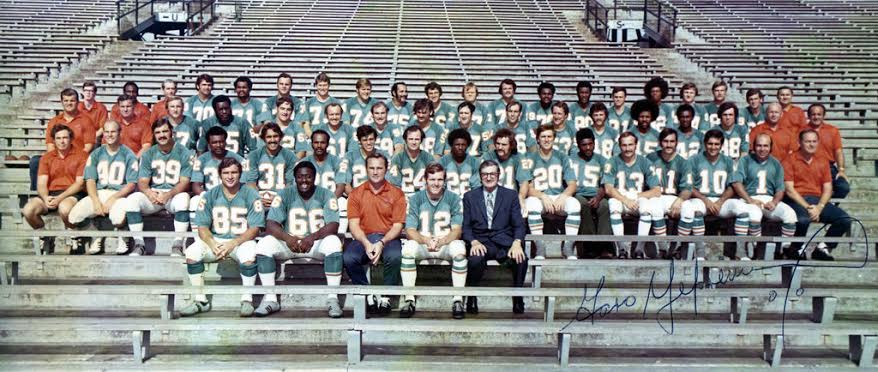

Reflecting back on that essay at thirteen years old, I remember being fascinated with the Dolphin colours – turquoise and red – and I distinctly remember a civic pride in Miami that I had not seen in my few years as a sports buff. I described the city being awash in Dolphins colours, right down to the light posts and city buses.

Was I able to ascertain a quantifiable difference in teams and athletes that earned “perfection” in that 1973 essay? No way. And, after five decades of being an addicted and practicing sports junkie, I have more questions than answers about what separates perennial champions from perennial contenders.

Indeed, I am perhaps a product of being raised with the Montreal Canadiens. The Habs are the second winningest franchise in the history of professional sports, with twenty-four championships. This is bridesmaid only to the NY Yankees, with twenty-seven. By the time I left Montreal for Seattle at age twenty-four, I had witnessed eleven Stanley Cups. One every other year on average. My favorite era was the four straight cups in the mid-'70s. I drank lots of beer, watched lots of hockey, and had lots of fun.

When I arrived in Seattle, I scolded people left and right for their tolerance of losing. I warned them not to become Toronto Maple Leafs fans, who never expect to actually win anymore! I don't know why, but there are indeed “cursed” teams that always seem to pry defeat from the jaws of victory.

I told my friends that once they had experienced a Super Bowl or World Series, they would never go back. They would never accept being mediocre again. The joy of your own team winning a championship is so amazing, and my Seattle buddies only embraced my theory after our Seahawks finally won the Super Bowl in 2013.

I also embraced my friends who were die-hard Boston Red Sox and Chicago Cubs fans after they finally won championships. These precious souls had experienced endless, humiliating, and depressing droughts of losing, and I was thrilled for them to feel the joy of winning.

I don't pretend to have a brainstorm formula of what separates contenders from champions in sports, or in life for that matter. But at the same time I believe there is something different. Perhaps team culture of winning and intolerance of losing, perhaps the stars aligning in uncontrollable areas such as schedule or injuries, perhaps momentum, perhaps ownership or management genius, perhaps other invisible factors.

But one thing I must admit, and will never claim otherwise; in sports, there is always, always an element of luck. Of unpredictability. Of tragic human failure, or jaw-dropping victory. It always seems that champions are hitting on all of the cylinders above, at precisely the right moment, and with a wink and a nod from Lady Luck.

But when I think about these 1972 Dolphins, or Tom Brady, or Jean Beliveau, there still seems to be something different.

It is what I describe as a Magic that seems to follow a victorious team or player to the mountain top. To the top rung of Maslow's Heirarchy of Needs. Watch any close championship struggle and you will know what I mean about magic.

Whatever quantifiable difference a Maslow Award winner has from the rest of us mortals might always be elusive. Or maybe the answer just rolls out with the tide, as soon as we think we're close.

But there is a bit of a joy in this mystery. It is what makes sports sports. And life achievements fleeting.

But there is something different, I do believe.

And I will certainly keep you posted.

Copyright © 2017 by Greg Meakin

GregMeakin.com

GregMeakin2020@gmail.com

A few weeks ago, I contacted my old publisher friend and writer extraordinaire, Lary Coppola. Lary and I go back to the ancient times of 1980s Kitsap County, near Seattle, and whenever I want the opinion about anything that involves the written word, I touch base with Lary.

Not only was Coppola publisher and primary writer for the legendary Kitsap Business Journal, an intellectual magazine that was a Must Read every week, but he's been a mayor, and a port commissioner, and is an all round active and successful guy in his community.

When awarding the 1972 Miami Dolphins Maslow Award, I reached out to Lary because he lived in South Florida at that time, and as is customary with my awards, I always want a boots-on-the-ground take. In 1972, as an eight grader in Montreal, I could only watch the Dolphins from afar, via lousy quality color TV.

But Lary Coppola was there. A twenty-two year old rabble-rouser I can only assume, and writes about his point of view of his 1972 Miami Dolphins.

As ever, Lary brings entertaining detail about that magical season, and also personalizes this reflection to today's Seattle Seahawks, and today's NFL for that matter.

The Fins. Those Perfect Fins.